Jun 26, 2019 | Sesotec

Plastic: part of the problem…part of the solution - Part 1: a global problem

Some 70 years after the first plastic products hit the market, the vision of a world without plastic waste still appears far off. Yet this substance – a plague once it becomes waste – is an extremely attractive material. What we need is a different approach to dealing with plastic waste. In this multi-part series, we will take a look at the role that the waste management and recycling industry can play in the process. Part 1 takes us to a variety of destinations, including China.

The

production of plastic has increased dramatically around the world in recent

decades and currently stands at 200 times the amount manufactured by factories

back in 1950. Europe is

responsible for one-quarter of the world’s plastic consumption, mainly due to

packaging that lands in the rubbish bin after being used for only a short time.

Plastic is also used in construction (20%), vehicles (8.6%) and electronics

(5.7%).

China and the EU up the pressure

Even today, used plastic is often considered to

be refuse and is seen as a problem that can be taken care of by simply throwing

it away. In recent years, a large amount of used plastic has been shipped to

China, destined for what many believed was a solution. Roughly 51% of the

world’s plastic waste, or 7.5 million tonnes, ended up in China in 2017. At the

time, China was the world’s largest importer of plastic waste. Transporting

waste there by ship, and then loading the ships with new consumer goods for the

journey back to their home countries, was long seen as a profitable business

model. However, this cycle has since been made more difficult by China’s

National Sword initiative. What is the idea behind it?

In January 2018, the Chinese government stopped

the import of low-quality plastic waste as part of its National Sword programme.

Only plastic waste with a purity level of 99.5% or more is still allowed into

the country. China no longer wants to act as a dumping grounds for other

countries. The Asian countries that subsequently stepped in at short notice to

take on the waste have been overwhelmed and will eventually issue their own

bans on imports. As a result, they are not a solution to the current problem,

presenting the waste management and recycling industry with a number of

challenges. Finding alternatives is an absolute must.

The EU has also acknowledged the problem. In

early 2018, it adopted a plastics strategy, stating that all plastic packaging

must be either reusable or recyclable at low cost by 2030.

The strategy poses another challenge for the

waste management and recycling industry that ultimately places it in the same

position as China’s National Sword initiative: ensuring the utmost purity of

plastic waste prior to its recycling and reuse – an essential part of its

ability to be employed as a secondary raw material.

Plastic – and no end in sight

The first plastic product hit the market in 1950. At the time, the world

produced around 1.5 million tonnes of plastic every year. In 2017, that figure

stood at roughly 350 million tonnes annually. A total of 8.3 billion tonnes of

plastic were manufactured between 1950 and 2017. China is the largest producer of plastic (26%), followed by Europe (20%)

and North America (19%). According to estimates from Plastics Europe, plastic production is set

to increase to 1,124 million tonnes.

A floating problem

The world’s oceans are already home to 150

million tonnes of waste. Three-quarters of it is plastic waste, and 1 million

tonnes is added to that amount every year. Many living creatures die a painful

death as a result. So far, little research has been performed on the effects that

plastics in the world’s oceans can have on the health of humans, who are

exposed to it through the food chain. But what has been proved is that plastics

take 350 to 400 years to decompose.

Packaging material disposed of along the

shoreline, residues from rivers and fishing waste, such as leftover nets or

ropes, are the main causes of marine pollution and the suffering of many marine

organisms.

The long-term goal must be to avoid marine plastic

waste entirely. However, creating a circular economy and recognising the value

of material that is widely considered to be refuse will be essential to

achieving this aim.

Tracking down marine debris

Plastic waste is mainly concentrated in five regions: in the north

Pacific, Indian Ocean, south Pacific, north Atlantic and south Atlantic. In

each region, the waste gathers close to the equator, where various water

currents and temperatures converge.

The largest patch of floating debris is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

in the northern Pacific Ocean, with an area of roughly 1.6 million square

kilometres and an estimated 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic.

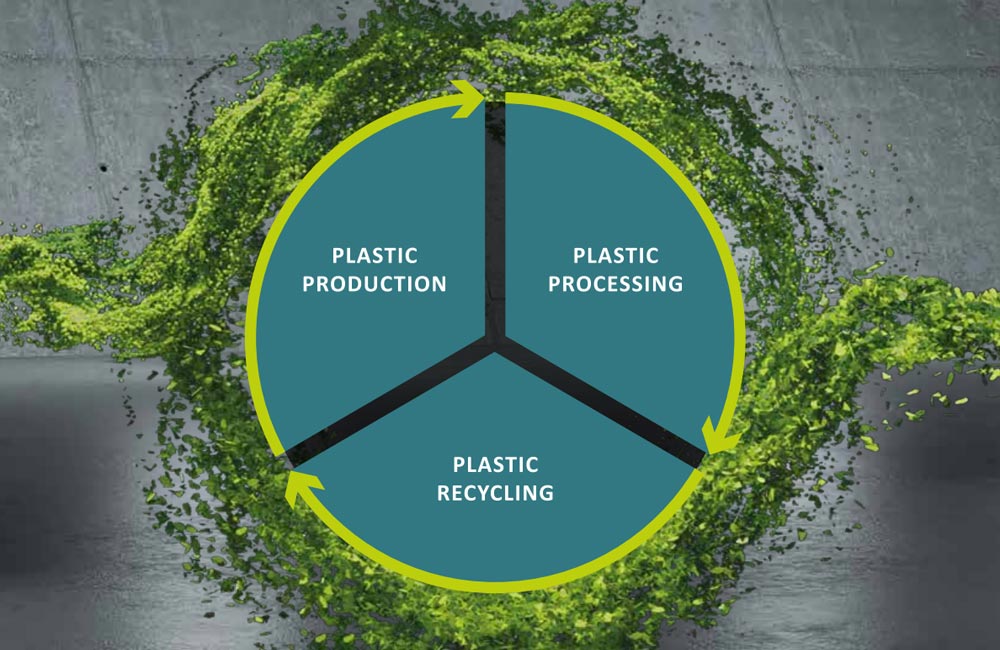

Purity matters

With plastic consumption and waste constantly on

the rise, fast and efficient methods of recycling and reuse at the locations

where waste is generated are of the essence.

A new way of thinking and a new approach are

also necessary from a sustainability perspective.

Plastic waste can no longer

be seen as rubbish. In times of dwindling fossil resources, it is a valuable

commodity. Top-quality recycling material is the key to

top-quality reuse.

Read the other parts of this series here: